I. RELIGIOUS POETRY

3. Old English Christian Poetry.

Religious poetry seems to have flourished in northern England-Northumbria-throughout the eight century, though most of it has survived only in West Saxon transcriptions of the late tenth century. Monks produced not only manuscripts, masonry, sculpture and missionaries but also a lot of Christian poetry. Much of it consists of retellings of books and episodes from the Old Testament. Much of this religious poetry is anonymous, but the names of two poets are known: CAEDMON (d.c. 670), the first English poet known by name, and CYNEWULF (late eighth or early ninth century). They wrote on biblical and religious themes. According to Bede Caedmon became the founder of a school of Christian poetry and the he was the first to use the traditional metre diction for Christian religious poetry. This period of Old English poetry is called "Caedmonian". All the old religious poems that were not assigned to Caedmon were invariably given to Cynewulf, the poet of the second phase of Old English Christian poetry. With Cynewulf, Anglo-Saxon religious poetry moves beyond biblical paraphrase into the didactic, the devotional, and the mystical. The four Anglo-Saxon Christian poems which have the name of Cynewulf are Christ, Juliana, Elene, and The Fates of the Apostles. All these poems possess both a high degree of literary craftsmanship and a note of mystical contemplation which sometimes rises to a high level of religious passion. One of the most remarkable poems written under the influence of the school of Cynewulf is The Dream of the Rood,by some it is attributed to the same Cynewulf, Andreas, and The Phoenix. Another significant Anglo-Saxon religious poem is the fragmentary Judith .The final part of Guthlac, a poem of 1370 lies, is probably Cynewulf's.

4. Latin Writings: Bede and Alcuin.

The most important Anglo-Saxon Latinist Clerks were the Venerable Bede(673-735)

and Alcuin (735-804); both came out of Northumbria. To them and to those

like them English Literature owes the preservation of the traces of primitive

poetry.

The Venerable Bede tells us that he was born in 673 and brought up in

Wearmouth Abbey. A few years later he moved to the monastery of Jarrow

where he spent his whole adult life. He was the most learned theologian

and the best historian of Christianity of his time. He was a teacher and

a scholar of Latin and Greek, and he had many pupils among the monks of

Wearmouth and Jarrow. He wrote the Historia Ecclesiastica Gentis Anglorum"(Ecclesiastical

History of the English People) and finished in 731. By that year he had

written nearly 40 works, mostly biblical commentaries. Bede died in 735.

Alcuin was Charlemagne's collaborator from 790 onwards. He was brought

up in York Alcuin left his country when the earliest civilization of the

Angles was about to be destroyed, because the Danish invasions, which

ruined monasteries and centres of learning, were beginning. He wrote liturgical,

grammatical, hagiographical, and philosophical works, as well as numerous

letters and poems in Latin, including an elegy on the Destruction of

Lindsfarne by the Danes.

"I DON'T KNOW HOW TO SING"

Bede's History is the first account of Anglo-Saxon England ever written. Bede was a monk of Jarrow who worked on this book for several years before completing it in 731. Over the next fifty years it was copied in Northumbria and elsewhere, and it became widely diffused in Western Europe throughout the Middle Ages. It was first printed in 1480. The History is readable and attractive. He writes of the geography of Britain, the coming of Augustine, the Northumbrian council concerned with the acceptance of Christianity or the achievements of Abbess Hilda and the poet Caedmon. The following extract tells the story of how Caedmon discovered he possessed God's gift for poetry. [A.D. 680].

In this monastery of Streanaeshalch lived a brother singularly gifted

by God's grace. So skilful was he in composing religious and devotional

songs that, when any passage of Scripture was explained to him by interpreters,

he could quickly turn it into delightful and moving poetry in his own

English tongue. These verses of his have stirred the hearts of many folk

to despise the world and aspire to heavenly things. Others after him tried

to compose religious poems in English, but none could compare with him;

for he did not acquire the art of poetry from men or through any human

teacher but received it as a free gift from God. For this reason he could

never compose any frivolous or profane verses; but only such as had a

religious theme fell fittingly from his devout lips. He had followed a

secular occupation until well advanced in years without ever learning

anything about poetry. Indeed it sometimes happened at a feast that all

the guests in turn would be invited to sing and entertain the company;

then, when he saw the harp coming his way, he would get up from table

and go home.

On one such occasion he had left the house in which the entertainment

was being held and went out to the stable where it was his duty that night

to look after the beasts. There when the time came he settled down to

sleep. Suddenly in a dream he saw a man standing beside him who called

him by name. "Caedmon", he said, "sing me a song."

"I don't know how to sing," he replied." "It is because

I cannot sing that I left the feast and came here." "What should

I sing about?" he replied. "Sing about the Creation of all things,"

the other answered. And Caedmon immediately began to sing verses in praise

of God the Creator that he had never heard before[...] When Caedmon awoke,

he remembered everything that he had sung in his dream, and soon added

more verses in the same style to a song truly worthy of God.

(Taken from: Bede, Ecclesiastical History of the English People, Chapter

24, Translated by Leo Sherley. Price, Penguin Books, 1990.

EXERCISE

1. Read the extract from Bede's History and write a summary of the story

of Caedmon. Paraphrase Caedmon's Dialogue with the man he saw in his vision

and use reporting verbs in the past tenses.

5. Old English Prose: Alfred.

The glory of Alfred's reign is Alfred himself(849-901) writes George

Simpson. It was under his influence that the earlier poetic works, which

had almost all been written in the Northumbrian dialect, were transcribed

into the language of the West Saxons. King Alfred played an important role

in this literary movement. He surrounded himself with scholars and learned

men, learnt Latin after he was grown up, and began to translate the works

which seemed to him most apt to civilize his people. In this way he became

the father of English prose-writers. He himself is credited with a translation

of the Universal History of Orosius. He translated (or ordered to translated)

Bede's Ecclesiastical History of the Angles. Much more important, and

among the best of Alfred's works, is the version of Boethius De Consolatione

Philosophiae. The first great book in English prose is The Anglo-Saxon

Chronicle, inspired though not written by Alfred. In some monasteries

casual notes of important events had been made; but under Alfred's encouragement

there is a systematic revision of the earlier records and a larger survey

of West Saxon history. The great Anglo-Saxon Chronicle is a series of

annals which start with an outline of English history from Julius Caesar's

invasion to the middle of the fifth century and continues to 1154.

Another important prose work and source of information about King Alfred's

life is a short biographical work, th the Life of King Alfred,written

in Latin and attributed to Asser (d. 910), Bishop of Sherborne (892-910),

whom Alfred called from Wales to aid him in the re-establishing of learning

also wrote a Chronicle of English History for the years 849 to 887.

READING

THE ELEGIAC

MOOD

The elegiac mood wells up, then, in a great number of Old English poems.

But the six so-called Elegies are poems where the topic itself is loss

- loss of a lord, loss of a loved one, the loss of fine buildings fallen

into decay. They are all to be found in the Exeter Book, a manuscript

now in Exeter Cathedral Library.

At the heart of Anglo-Saxon society lay two key relationships. The first

was that between a lord and his retainers, one of the hallmarks of any

heroic society, which guaranteed the lord military and agricultural service

and guaranteed the retainer protection and land. The second was the relationship,

as it is today, between any man and his loved one, and the family surrounding

them. So one of the most unfortunate members of this world (as for any)

was the exile, the man who because of his own weakness (cowardice, for

example) or through no fault of his own, was sentenced to live out his

days wandering from place to place, or anchored in some alien place, far

from the comforts of home. This is the situation underlying four of the

elegies.

(Taken from:Kevin Crossley-Holland, The Anglo-Saxon World. An Anthology,Oxford

University Press,1984.)

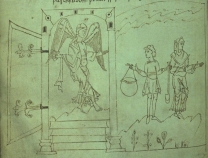

CAEDMON AND CYNEWULF

Caedmon, (flourished 670), entered the monastery of Streaneshalch (Whitby) between 658 and 680, when he was an elderly man. According to Bede he was an unlearned herdsman who received suddenly, in a vision, the power of song, and later put into English verses passages translated to him from the Scriptures. Bede tells us that Caedmon turned into English the story of Genesis and Exodus. The name Caedmon has been conjectured to be Celtic. The poems assumed to be Caedmon poems Caedmon are: Genesis, Exodus, Daniel, and Christ and Satan. But critical research has proved the ascription to be impossible. Perhaps the Caedmon songs were used by later singers and left their spirit in the poems that remains; but of the originals described by Bede we have no trace. The only work which can be attributed to him is the short "Hymn of Creation," quoted by Bede himself. This is all we possess of the first known English poet. It survives in several manuscripts of Bede in various dialects.

Cynewulf:

Cynewulf (late 8th or 9th century) was identified, not certainly, but probably, with a Cynewulf who was Bishop of Lindisfarne and lived in the middle of the eighth century. He was a wandering singer or poet who lived a gay and secular life. The accuracy of some of his battle scenes and seascapes showed that he had fought on land and sailed the seas. Finally, after a dream in which he had a vision of the Holy Rood, he changed his life, became a religious poet, sang of Christ, the apostles, and the saints. His work represents an advance in culture upon the more primitive Caedmonian poems. The poems attributed to him are: Juliana, Elene, The Fates of the Apostles, and Christ II.

CAEDMON'S HYMN

The following nine lines are all of what survives that can reasonably be attributed to him. Bede quotes them in Chapter 24 of his History. Bede adds that these lines are only the general sense, not the actual words that Caedmon sang in his dream. Caedmon's gift remained an oral one and was devoted to sacred subjects.

"Now must we praise"Now must we praise of heaven's kingdom the Keeper

Of the Lord the power and his Wisdom

The work of the Glory-Father, as he of marvels each,

The eternal Lord, the beginning established.

He first created of earth for the sons 5

Heaven as a roof, the holy Creator.

Then the middle-enclosure of mankind the Protector

The eternal Lord, thereafter made

For men, earth the Lord almighty.(658-680)

EXERCISE

1. Read Caedmon's Hymn and say what the poet sings about.

2. Look up the word caesura in your glossary and give its definition.

3. Look at the layout of the poem and comment on the composition

of the lines.

4. Write a short summary of this modern translation of Caedmon's Hymn.